PRESENT FOREVER is the new go-to source for exploring independent clothing brands, makers and stores from across the globe

If the lightness of being would have a scent it would be that of lavender.

The English word came into use in the 13th century, and is thought to derive from the Old French lavandre which, in turn, comes from the Latin lavo (“to wash”) — referring to a practice, common before the invention of soap, where blue infusions of lavender and wild sweet William (or “soapwort”) were used for bathing and washing. Lavender has been a basic ingredient of “folk” remedies for many centuries. It was traditionally considered to be antiseptic, strewn on floors and burnt in sickrooms to deter infection, and believed to cure toothache, headache, and palsy. Even today, the human use of lavender’s chemical features sparks medical and pharmaceutical innovation, and it’s endorsed by official health organizations as a treatment for anxiety and insomnia.

An undemanding garden plant, needing minimal feeding or watering and flourishing in dry soils in full sun, Lavendula (its official taxonomic name) is found across the entire globe — from the Balkans, Levant and coastal North Africa to parts of Eastern and Southern Africa and the Middle East, and from South Asia to the Indian subcontinent.

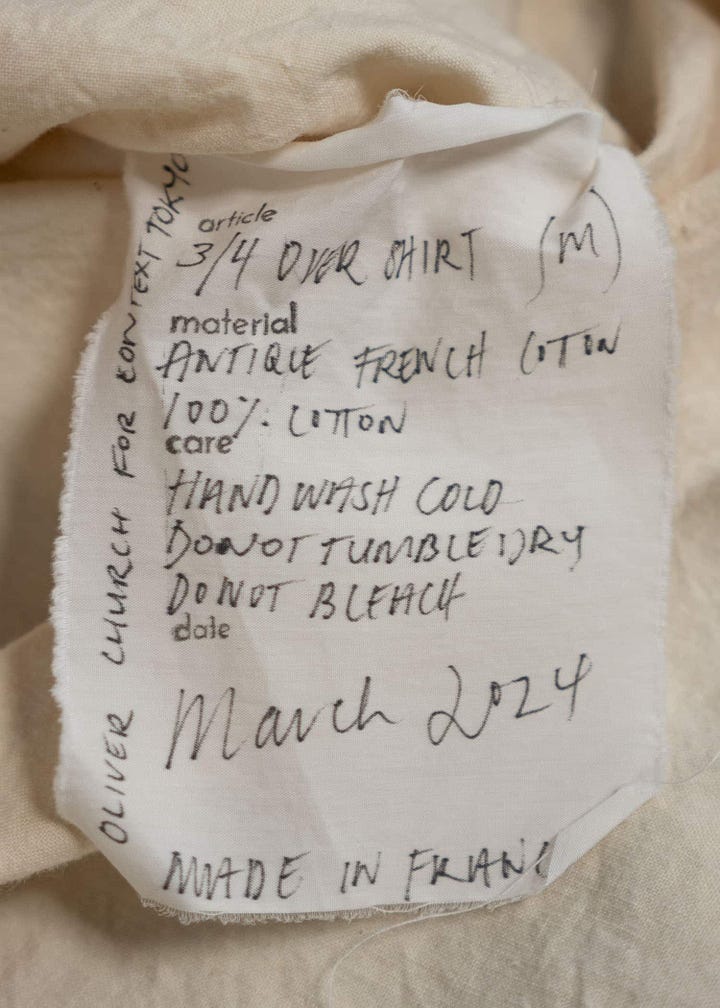

For Oliver Church — the Paris-based clothes-maker/designer who worked at Casey Casey before launching his eponymous label — lavender is what connects his native New Zealand with France, his new homeland since six years of which he’s in the process of becoming a naturalized citizen. There’s a small dried lavender bundle on a nail on his studio’s wall, giving off a subtle scent reminiscent of his youth in Waitakere. Some of his handmade, hand finished items have a one-of-a-kind lavender embroidery, done without a template and entirely hand-stitched with four different colored threads, on a jacket’s chest pocket or — a bit more hidden, in the form of a stem — on the back of a shirt’s collar.

On the morning of my third day at Paris Fashion Week, I took metro line 13 in the direction of Châtillon Montrouge. After a 40-minute ride, I got out at the final stop, and followed the instructions Oliver had sent me. “The door is behind the bus stop. If it’s open come through and I’ll see you. If it’s not give me a buzz.” I found the gate open, entered the courtyard, but wasn’t seen by anyone except for a blackbird sitting on a fence. I buzzed Oliver, who replied, saying he forgot a bag (filled, as it turned out, with a batch of fabric) and had to bike back home to fetch it.

We entered the building — an unassuming, perhaps not gloomy but definitely slightly desolate commercial property turned creative breeding space. After walking through a few dimly lit corridors, we arrived at Oliver’s studio: a 16m2 space with two tables (one for sewing, another for ironing), a rack with some dozen pieces (some worn-in, others with minor errors), a bookcase, a few unopened bottles of red wine, and a lot of fabric (in bulging boxes as well as on the floor beneath the ironing table). This, I immediately realized, is a monkish place of painstaking devotion, of spiritual commitment — not to some higher transcendent aim, but to physical activity of cutting, sewing and finishing garments. And, I came to understand a bit later into our almost two-hour conversation, it’s exactly because of its earthly, this-worldly nature that the work has this almost other-worldly aura.

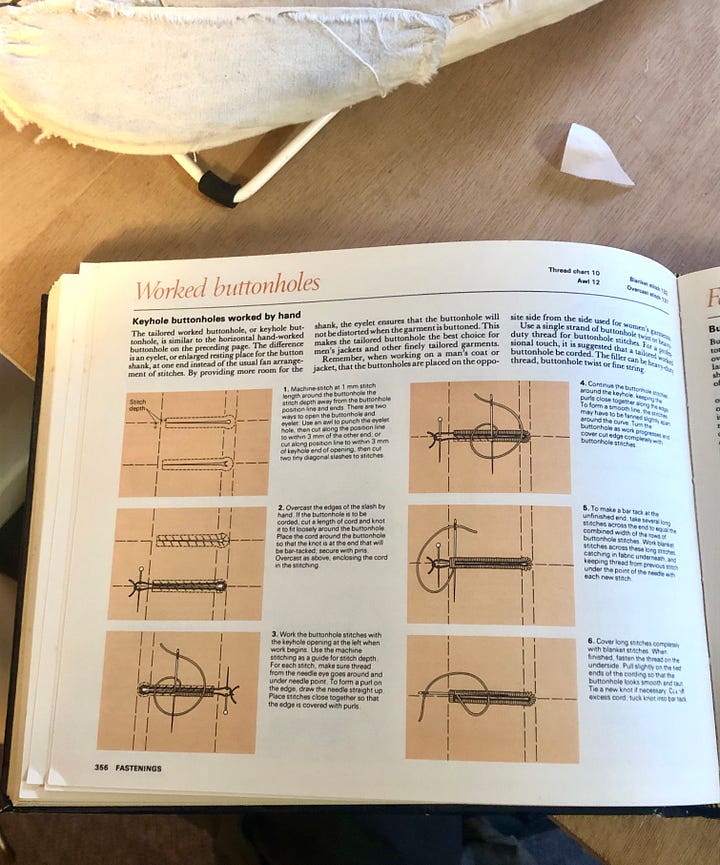

There’s no mystery to what Oliver does. I saw it happening right before my own eyes. He sits on an old office chair behind the table with his sewing machine. Sometimes he stands up, turns around and walks the 1,5 meters to the other table to press the seams, only to walk back and continue sewing. That’s what he does eight or ten hours each and every day. (I have to stick to the facts: Oliver told me he’s trying to reduce work hours, and take more than one day off.) When he’s not sewing and pressing seams, he’s either hand finishing an item, hand crafting a buttonhole, doing an embroidery, or dyeing the antique and vintage fabric — between 50 and 120 years old — he has sourced himself from markets around Paris.

The fact that there’s no mystery to what Oliver does is what makes it very mysterious— in the world as we know it, at any rate. His working methods are at odds with, no, are incompatible with the fashion industry’s traditional business model. Both through what he does, and how he does it, he’s bringing something into existence that shouldn’t be able to exist. The quantities are limited to a mere fifteen to twenty pieces a month — each typically takes ten hours to make — and are all made to order. There’s no desire for commercial growth. In fact, it’s downsizing rather than expansion that seemed to be on Oliver’s mind when I spoke to him. This undoubtedly to the disappointment, if not despair of the handful of carefully selected stockists he works with. What’s more, he combines his deliveries for Neighbour, Mouki Mou, Vision of Fashion, Rennes and a few other stores with private orders, and always keeps a small, sporadic number of pieces available on hand for direct sale.

None of what Oliver does is suitable to any kind of serious up-scaling, let alone industrialization. That’s partly because it cannot be standardized. The old fabrics he works with are in used condition and come with faults and defects, marks and wear. Another reason is that it’s entirely personal. This also includes decisions about which fault or defect to embrace as natural and which to consider as a man-made error and/or as rendering a piece defective.

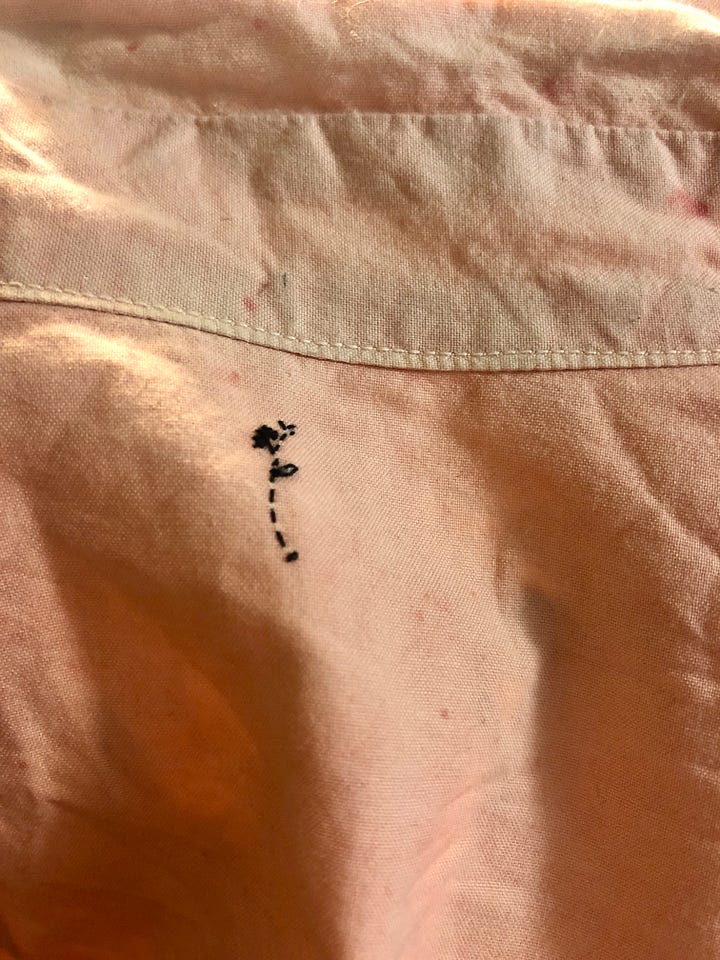

Here’s one example. For pieces bought direct, Oliver offers a re-dye service, in the hope that this prolongs the piece’s life and use. (Here he gives advice on how to care for your garments so they can age gracefully.) However, certain mordants can bring out marks and stains which, he explains, “happens all of the time at different degrees” with the fabrics he uses. He himself is accepting of this process, but knows — and wants customers to know — it’s a risk/reward scenario. Another example. During my visit, Oliver showed me two finished pieces where, according to himself, he made a mistake — a misplaced buttonhole (by 15-20 millimeters, I’d say) and a slightly wobbly seam, due to tiredness.

It’s characteristic of Oliver’s philosophy, as I see it: natural faults are to be expected and encouraged, whereas man-made faults are to be avoided through expert skill. His singular garments exist at the crossing of these paths — they’re what happens when pure coincidence and hard-won meticulousness meet to bring a piece of fabric come alive.

And the expertise and skill Oliver brings to the table are second to none. There’s no cutting corners. There’s no excuses. There’s no make-do. Instead, there’s a “physical approach” to clothes, with the thinking taking place in and through the doing. There’s a constant process of self-learning of new crafts and techniques, from thread embroideries to worked buttonholes. And there’s a dedication, as I see it, to a kind of goodness that envelops but also goes beyond quality. The jackets and shirts, as well as the occasional trouser and upcoming knitwear piece, he makes are good in the sense that their high quality makes you want to have them for yourself. They’re also good in another sense, however: it’s possible and enough to enjoy them exactly for what they are, to rejoice in the fact that they exist, irrespective of whether you possess them.

The truth of this statement became important to me at the end of my studio visit. Oliver was kind enough to offer me to purchase one of the items hanging on the rack: if I’m not mistaken, it was a ‘Scalloped Shirt’ in super soft, light pink Japanese plain cotton, dyed naturally by hand using madder/garance, with hand-sewn gussets at hem/side seam and buttonholes finished with reclaimed shell buttons. As soon as I tried it on, I knew I wanted to live the rest of my life in this shirt, as if it had just been hanging there to become part of it. I was ready to say “yes,” irrespective of the price. When Oliver told me the price, I realized I had to postpone my decision. Not because the price was too high. But because I suddenly knew, no, because it dawned upon me that the shirt’s significance existed independently of my possession of it. I could buy the shirt, but in doing so I wouldn’t be buying what it meant to me.

After leaving the studio, and walking back to the metro, I found a few buds of dried lavender in my back pocket that my daughter had put there last summer. Their distinctive soothing scent started to blend with my impressions and thoughts of Oliver’s garments. What emerged was a feeling of incredible lightness. I couldn’t tell whether it was the lavender, the summer memory of my daughter, the radiance of the clothes I had just seen, touched and worn, or the joy of a surprisingly pleasant conversation. It didn’t matter. It was all these things together — each so simple, and yet so powerful, so unassuming, and yet so exactly right.