The Uninterviewable

Why talk (to me) if your work speaks (to everyone)?

Since starting Present Forever — about a year and a half ago now — I’ve been sending out interview requests almost every other day. I don’t have the exact numbers, but it definitely runs in the triple digits.

I feel lucky and blessed that so many of these get accepted, and even when they’re politely declined I can’t feel bad about it. Often one or the other thing involved in running a brand takes priority — of course! It’s more important to create new designs, test samples, or get orders ready for shipping than to talk about creating new designs, testing samples, and getting orders ready for shipping. Not always, but almost always.

There’s another category altogether that needs to be addressed: brands that don’t do interviews — not because they lack the time, but because they simply don’t want to, and because they won’t make the time. Let’s call them the uninterviewables.

Before getting into that, one major proviso is in place: when I say they don’t want to do interviews and won’t make the time, I mean that many of them probably don’t want to do one with me — or make time for me. That’s both a humble and a seemingly judgmental statement. It’s humble because — your ongoing, fantastic, and growing support notwithstanding — this newsletter is microscopic and without much cultural or institutional power to boast. Who knows, this might change someday, somehow (and salute to that future, by the way!) but no, not yet. It’s judgmental because it suggests that these brands are in the wrong for not making time for non-big platforms. I don’t believe they are, for why should they?

Of course, it wouldn’t hurt for any commercially successful brand or designer to talk to platforms that aren’t directly instrumental in further boosting their fame or commercial success — even if it’s just to return to their roots or touch base with early supporters. Yet, the global market’s painfully funny logic makes that almost impossible to imagine.

That said, let’s look at the bright side. There’s a lot to be learned from the different ways brands neglect or ignore or dismiss one thing while prioritizing the other — at least if your goal is to make sense of this thing called fashion. Every fashion theorist — self-declared or academically tenured — may study as many interviews as they like, but it’s the uninterviewable they should really be after. As Peter Burke once put: the historian of sound will at some point also have to study silence. And it’s much the same here.

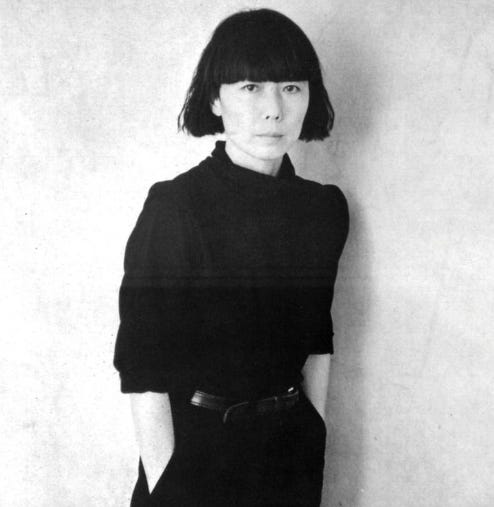

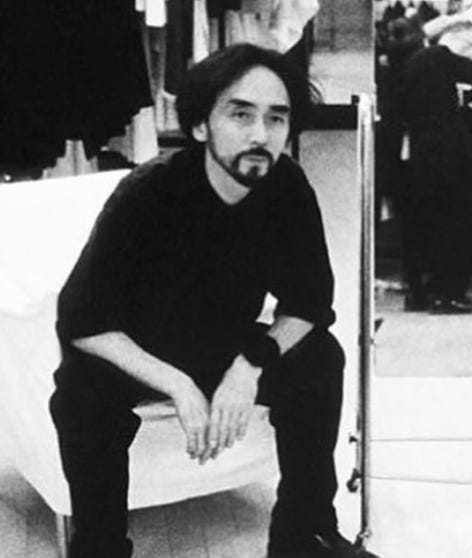

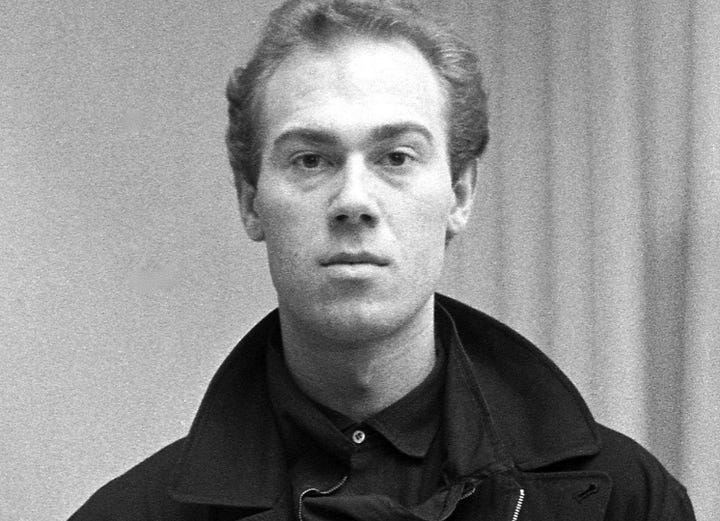

There are famous examples of designers who rarely, if ever, gave interviews, of course: Margiela, Kawakubo, Yamamoto, Margaret Howell, and a few others. Their reasons have ranged from conceptual radicalism — like Margiela’s anti-celebrity ethos — to aura-creation, as with the enigma that is Kawakubo, to selfless pragmatism, in Howell’s extreme focus on the garments. Some might see one or the other version of this as genuine and honest; others will argue it is secrecy and mystique for commercial gain.

That’s a different debate. What I want to talk about is how uninterviewability happens from the perspective of the would-be interviewer — myself, in this case.

Take Auralee. I can’t reach them. That’s because I don’t know how, and I don’t know how because I’m not in touch enough — literally. I only have their info address, which isn’t meant for invitations, and when you’re silly enough to send an invitation there, you won’t hear anything back — ever. (I learned this the hard way.) Interestingly, that puts them in the same category as a range of extremely different brands, like Kaval, Somafolk, Vu, Beaugan and others, many of which have neither a website nor an info address.

Another example of a different type: Rier. Back in December 2024, when I was working on the Tyrolean Futures-series, someone at Rier (Andreas Steiner?!) wrote me a line on IG in response to an interview request, saying: “We will have a conversation, but communication goes through our press agency, Radical PR.” Long story short, RadicalPR informed me they couldn’t accommodate the request. (They did truly appreciate my understanding, though — for which many thanks.) I wrote Rier another direct message shortly after, and never heard back.

A slightly different example of the same type is Casey Casey. After a message on IG from the team, accepting the request, I followed their instructions and sent an email with a first round of questions. About a month later, I received a kind reply saying that Gareth Casey himself wasn’t available to answer the questions himself but that the team would be happy to respond to “less Gareth-specific questions.” I passed on that offer, and decided to check in again in a few months, around last July. A reply came later that month: “We are a small team, with no PR resources. We should be able to answer your request soon though, so let’s reconnect in October.” And we did. The outcome: the option of having an exchange with a member of an external party who knows “how to share our story.”

This makes you wonder: is this exchange about Casey Casey an interview with Casey Casey? Is such an exchange an interview at all? I don’t know — which explains why I’ve yet to respond.

Then there’s the case of Comoli — the Tokyo-based brand founded by designer Keijiro Komori which — like a darker, quieter brother of Auralee — has been making waves since 2011 with familiar utilitarian, military and sportswear silhouettes done in sumptuous materials that give them the hand-feel of pure garment bliss. Most telling of their cultish rejection of attention is that the recent launch of its IG account made Highsnobiety headlines. (Before that, there was only this unofficial account which, by the by, still has more followers than the brand’s own account.) Komori has done some interviews in the past (like this one), but very sparingly, and only in Japanese publications. But clearly his intent with Comoli has been to let the clothes do the talking — without promotion, without fanfare, without PR, without any images of himself — and it works wonders.

Yet another category is that of brands and designers who do respond to interview request, but kindly decline them — directly or indirectly. Here too, the reasons vary, and each one is telling of how they go about.

Take Philippe Vidalenc, once the other half of Casey Vidalenc, the brand Gareth Casey and he founded in 1997 and which was discontinued in 2008. Around that time, Gareth launched Casey Casey, and a couple years later, Vidalenz started Chez Vidalenc. Both have become known for luxurious, anti-luxury sculptural pieces with heavily oversized fits, yet where the former now enjoys a global presence, the latter confines to a small Paris atelier. Likewise, whereas Casey Casey works with a PR firm for interviews, Philippe Vidalenc takes a different approach: “Thank you for your email, Lukas. I never give interviews and I don’t need to be present on any website.” Too bad, of course, but the reason he gave made sense for a one-man operation: “I can’t produce all the orders I receive.”

So, limited capacity is one reason for a small maker to decline; another is the need to pause and reflect on next steps. After a couple back-and-forths, Pat O’Rourke from Bexhill Court — the label founded in 2023 whose limited drops of beanies sell out faster than can you say “scrap” — wrote that he preferred to postpone the interview to a later date. “I’m still figuring out what I’m doing with it next, and don’t know if I’m at a point to speak on the fine details of the brand just yet.” Bryn Bingham — the 24-year-old American designer I briefly profiled in July — finds himself at a similar point, though not quite: his label, Brynner’s, is yet to be officially launched. “I would love to have a conversation,” he wrote, “but I’m still getting everything ready for the launch later this year or nearly next year. Would that timeframe work you?” Oh, yes it does!

Valentin Rudloff, a Vienna-based amateur weaver involved in Pure Fabrications — a Danish-based project combining traditional craft with experimental designs — went even further. “It would be great to talk at some point in the future, but I need a bit more time to understand what the h*ck I’m doing. Let’s stay in touch!”

One other example from this category: Studio de Lostanges, co-founded by sisters Louise and Jeanne Tresvaux du Fraval, who make one “edition” per year in their workshop in Brittany, France. I visited their Paris showroom in June, and they remain one of the most promising brands I know: the aesthetic is second to none, and the singular vision (in brief: French seafaring gear made from deadstock and second-hand fabrics) is there. It all made me really eager to talk with them. They were kind enough to accept the interview invitation, I shared a first round of questions, and then…silence. A couple of reminders from my side followed, met with more silence. But who knows — maybe one day!

Lastly, Gabriela Coll, who falls into a category of her own, which also happens to be one of my favorites. Coll, known for combining technical know-how with a fine arts sensibility to create the most elevated of elevated basics, recently made it to Highsnobiety’s ‘Good Clothes Index’, and with good reason. As Chris from Duchump put it nicely: “The work feels less like conventional fashion and more like an ongoing art project — personal, imperfect, and deliberate.” Look at this ‘Corduroy Puffer Zipper Jacket’ and ‘Black Denim Shirt’, and sigh at your wallet.

When I asked Gabriela to answer a couple questions for an upcoming feature, her reply — “Sure!” — arrived within an hour or so. What happened next was something resembling a first attempt at an interview. Here’s an excerpt:

Lukas Mauve: The first thing that probably leaps out to anyone about your clothes is the intentional link between production and final piece — the noticeable traces of its origins in the garment. Why is that so important to you?

Gabriela Coll: “I’ve always had a special interest in the process of things. [Inserts link to Francis Alys’ performance Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing (1997)]. A prototype has a way of feeling alive, open. I wish I could translate some of this into the garments, to make them feel less dead and more linked with the process behind it.”

Lukas Mauve: Another thing that everyone familiar with your brand talks about: your use of the world’s finest fabrics — Loro Piana, Solibati, etc. From you bio I gather that the reason behind this choice has something to do with you interest in “the classical and inherent character of fabrics.” Could you help me understand what this character is?

Gabriela Coll: “Yes, sometimes the process leads me to these very established houses. What they do is classic — not seasonal, but archetypal.”

Lukas Mauve: You’ve been active for almost 10 years now — and you’re well-established but still a relatively small operation. A lot of new brands seem impatient to hit a massive scale very fast, whereas you seem to be playing a slower but longer game. How do you look at this?

Gabriela Coll: “To me it’s quite simple. It needs to make me happy. I need to believe in it. And I want to do it in my own way.”

Gabriela’s “own way,” as it turned out, was actually to not do any press or interviews. When I shared a few follow-ups, she replied: “I want to keep the focus solely on the clothes. Let me show them to you when we meet in person. No formal interview, just talk.”

And with that, I think she hit upon a real-life truth. It’s not so much fashion’s wordlessness. It’s this. The classic role of journalism is to question power, and one of the ways in which journalists do that is through interviews. Yet, although the interview remains fashion journalism’s favorite medium, they have also become the place where power is questioned the least. My editor at the Dutch newspaper I occasionally write for recently said that Present Forever isn’t journalism. I believe she’s right. But then again, I’m not even exactly sure what being right means here.

There are different approaches to questioning power. One is to put those in power to the test. Another is to shine a light on those with the power to do so. A conversation — a chat, a talk — with them can be a powerful way to make that happen. And when they don’t want to speak, the best alternative is to listen very carefully to what their work has to say.

Beautifully written as always

Love this one!