Not I (1972) is a short dramatic monologue written by the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett. It’s the one where almost the entire stage is in darkness except for the mouth of a woman, illuminated by one tight spotlight, moving at a breathless speed. If you haven’t seen it, watch Billie Whitelaw’s 1973 performance of it here:

From now on, Not I is also the name of a new pics-only weekly section, appearing on Thursdays or Fridays. It’s where I’ll share curated items from my saved favorites at the reselling platforms I browse every single day. I figured there isn’t a more fitting name than Not I. One reason is that, by sharing these hard-won finds with you, I’m making sure I won’t be the person buying them. That’s a good thing. Because I can’t afford to buy everything I like. And because I don’t need to or want to, even though I can easily convince myself of the opposite.

What’s to like about pre-owned clothes?

Let’s sum it up:

What’s not to like? Okay, here’s one major thing: you’re not using your money to support small brands

It helps you remember you’re not a cog in the capitalist machine. You don’t always need the newest of the newest. Your current wardrobe isn’t always already obsolete.

It encourages more rational financial behavior, and this behavior is directly proportional to the amount of sense it would make for most fashion brands to drop the seasonal model. Lemaire AW23 isn’t better or worse than Lemaire AW25. But if you can get a Lemaire AW23 piece for €150, rather than a similar one from AW25 for €750, that is better for you.

It allows for a less rational, more experimental approach to your wardrobe. It’s a virtue to think about the clothing you buy. But over-thinking it can be a vicious thing. Sometimes you just have to give it a try. I, for one, often wonder whether a poppy red crewneck could work for me. This And Daughter knit places a €475 abyss between me and sartorial experiment. A €25 Luciano Barbera piece — made in Italy from 100% cashmere — erects a make-do bridge allowing me to cross it.

And:

Pre-owned clothes open the door to this heavenly universe called vintage. A gift that keeps on giving, its benefits are potentially endless. (Except for hazardous chemicals like asbestos in clothes from the 1920s-70s, which are an oft-forgotten downside.)

Vintage pieces are often equally good or even better than new ones.

- They’re better because they were manufactured in a period before mass-production and -consumption. Hence: higher quality overall

- They’re better because they were often made in their country of origin with materials from that same country. Hence: more eco- and socio-friendlyBecause pre-1990s clothes were often not mass produced, vintage pieces from designers like Katharine Hamnett, Armani, Helmut Lang, and Massimo Osti are often in excellent shape and can be extremely hard to find. This is not just testament to their quality (there are French chore coats from the 1950s that are in better shape than yesterday’s fast-fashion release)…

…the fact that they’re hard to find also adds to their inherent uniqueness. They’re worn at the edges, there’s a name written on the tag, they’ve got paint splatters all over, they’re odd looking, they were gifted to the previous owner by the designer him- or herself, etc. All in all, there’s personality written all over it.

Some of the best vintage pieces out there tell a story about 20th-century fashion history. In fact, they’re sometimes the only material sources left. I’ve done quite a lot of research on Issey Miyake’s Plantation. The pieces I find online, as well as the owners I buy them from, are (no lie!) the only existing leads for writing about this now defunct brand from the 1980s-90s.

Last but not least: so much of what designers create today — and, as such, so much of what we’re buying and wearing — traces back to utilitarian, military, sports and outdoor gear from the 20th century. And these pieces come at a fraction of the price of your buzziest designer’s latest collection (as well as of the best curated second-hand stores). I’ve mentioned Rier’s precursors Geiger, Giesswein and Moessmer before, and I’ll do it again here.

What do you want to wear?

Noah Johnson — former GQ Global Style Director, Highsnobiety’s new Editor-in-Chief — ended his reflection piece on 2025 Paris Fashion Week with these words: “The thing about the future of fashion is that it’s actually pretty easy to predict [in brief: good clothes made by designers with a strong, singular vision, LM]. What remains uncertain is similarly straightforward: What do you want to wear?”.

I agree that this is uncertain — not just now, but forever. I wouldn’t say that it is straightforward, though. It’s the most difficult question there is, at least for us modern humans. We don’t know what we want. And, strangely enough, this doesn’t mean that we wouldn’t know what we want when put on the spot. It means that what we think we want isn’t always or necessarily what we really want. In fact, more often than not, it’s the exact opposite.

“Everything we think we want” is an ideological cabinet of curiosities: to it belong all those quasi-conscious things we do to create our identity, to acquire social status, to be recognized and accepted by friends and family, to live up to our own and others’ expectations of us, to fool ourselves into believing we are what we buy and become what we invest in. But that’s not what we really want.

Now, what do we really want to wear? That’s not a question of: do I like this sweater or these shoes? If anything, it’s an invitation to dig a little bit deeper — to find and cultivate the attitude from which we come to know our own needs. There’s no general answer to what our needs are. Your needs aren’t my needs, and vice versa. What your needs are depends, well, on who you are. And who you are, well, that’s a matter of inner, soul-searching experimentation of course.

This experimentation is not a process of addition or multiplication — that’s mostly self-suppression — but of subtraction — which boils down to ego-emptying. It’s about undoing, unthinking and unlearning. It’s about undoing what you usually do, breaking out of patterns of habit; about unthinking what you’ve come to believe about yourself; about unlearning skills, convictions and assumptions that help you survive and navigate. This takes some courage and honesty. It’s not particularly pleasant. And it’s never finished. The thing is that when all’s un-done, un-thought, and un-learned, you’re still there. Let’s call that your ego-emptied self. (And there’s that second reason for this new section’s title!) It’s what you find when you lose yourself. It allows you to surprise yourself. It enables you to do what, before, you did not think you would or could. It demystifies part of the mystery of true personal style — which may be just another word for the clothes you choose from this attitude.

What’s existentially significant about clothes is this double-sidedness: they’re like external facilitators of an inner process of which they’re also a material, tangible outcome. That, an any rate, is the premise of this new section.

Unlike a shopping or gift guide, Not I is not meant to say what you should buy, but to offer suggestions for what you could wear. There’ll be steals and good deals, for sure — a €125 Evan Kinori shirt or a €220 Casey Casey coat, say. But there’ll mostly be rare finds, quaint accessories, vintage gems, sample pieces, and items from forgotten, neglected or discontinued brands.

45R - ‘Indigo Dyed Leather Jacket’ (Size 3/M)

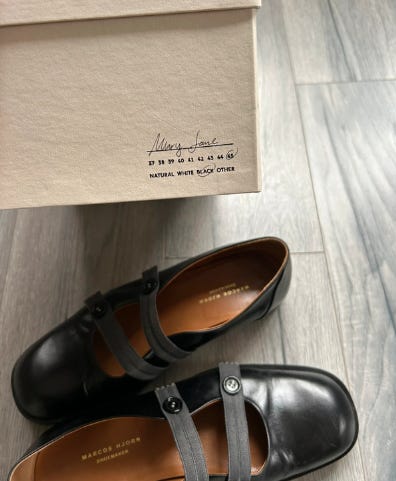

Marcos Hjorn - ‘Mary Jane’ (EU45)

Bergfabel - ‘Organic Cotton Shirt’ (Size M)

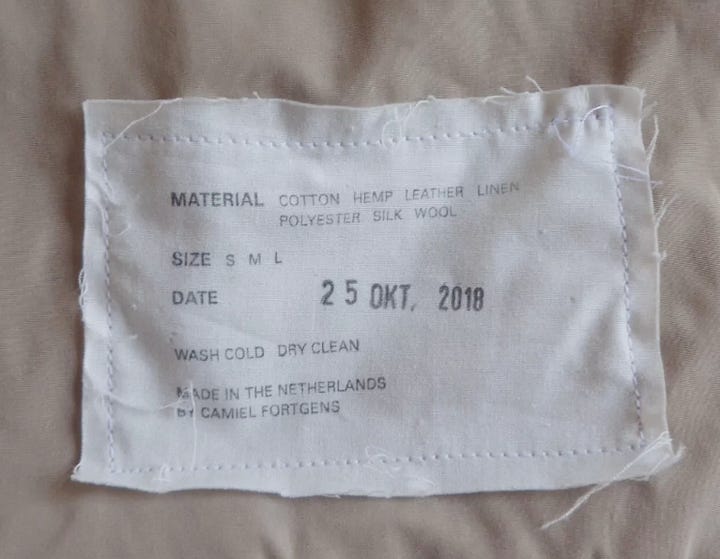

Camiel Fortgens - ‘2Way Shoulder Bag’

Eddie Bauer - ‘1960s Diamond Beige Goose Down Pants’ (Size M)

Carol Christian Poell - ‘Orange High-Tops’ (EU41-42)

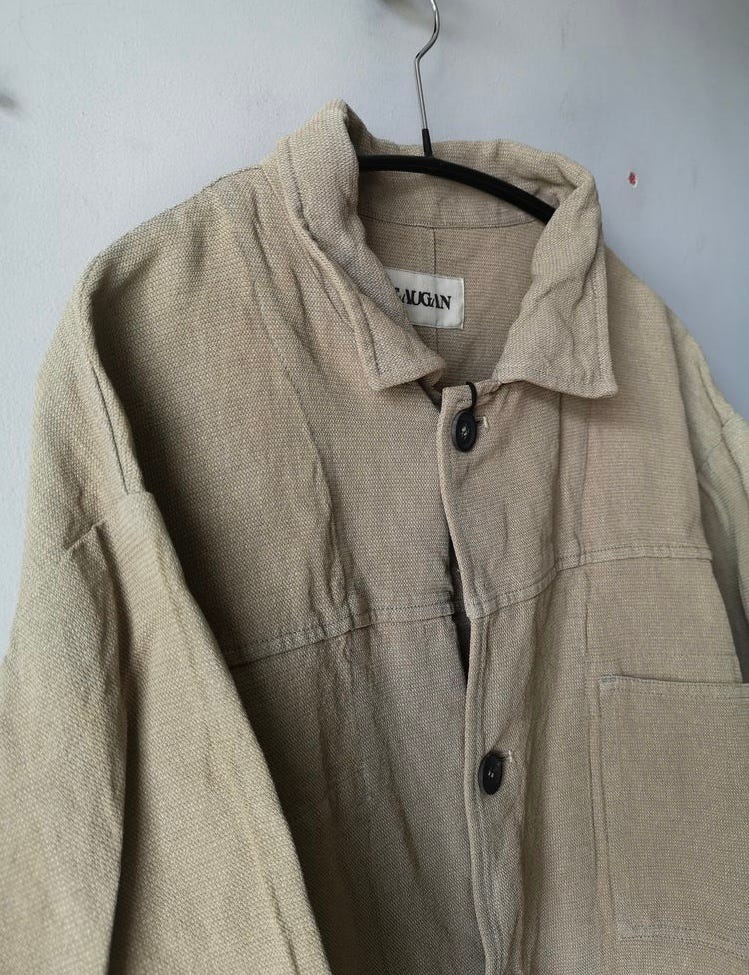

Beaugan - ‘Washi Paper Atelier Coat’ (Size 48/M)

Paul Harnden - ‘Red Waxed Cotton Anorak’ (Size 50/L)

Some items are only available in (part of) the EU. If you’re looking for one of these, please free to reach out via DM and I’ll do my best to help out

Wow, that Paul harnden anorak. ❤️🌶️ I often think about this in terms of the different decisions I make and pieces I end up choosing because I shop second hand. There’s a different sense of availability, each piece feels quite special to be found, and it may not have been the piece I would have chosen say I walked into the showroom and could have which ever piece I wanted. This sort of dance with my sense of exerting my control or will as personal style is one that I think opens up an internal conversation and questioning of that very premise. (That my personal style is this neat intention to outcome pipeline that I have complete control over. )

Thanks so much for sharing this, Liz. I love the phrase ‘senses of availability’ and ‘internal conversation’ to describe what’s happening and at stake here - so much of which is beyond our immediate control or conscious deliberation.