PRESENT FOREVER is the new go-to source for exploring independent clothing and style from across the globe. Please consider subscribing and/or upgrading to paid to help expand this off-beat universe:

It started with a boat.

The most human of human instincts is to categorize the world. The thing with categorizations is that all of them say less about the world than about the humans making them up. (Some, like that in Jorge Luis Borges’ ‘Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge’, exist solely to make this point.) Still, one categorization is better than the other. What makes a categorization good, scientifically speaking, is that it helps us answer questions about what the world is like. What makes a categorization good, culturally and existentially speaking, is that it helps us question answers about what the world is like.

We humans should sit down every once in a while — sometime, somewhere — and consider which of the categories we’re using are good and which are bad. A bad category is easily recognized. Rather than questioning answers, it provides answers that leave unasked, conceal or dismiss the questions it cannot answer.

“Fashion” may well be coming to belong to the category of bad categories. Gilles Deleuze, in a 1972 conversation with Michel Foucault, once said that a concept is like a box of tools. The same holds for a category. It must be useful. It must function. Its purpose is to do work. But what work is the concept of fashion doing in the attempt to understand the part of the world it carves out? Is it still useful when trying to grasp everything that’s happening under its name? On the one hand, fashion theorists struggle to define the concept. On the other hand, what started as a term originating from the Latin word for making (‘facere’) is now used interchangeably to capture a trillion-dollar global industry, aesthetics, social status, trends and outfits as well as clothing, footwear, accessories, cosmetics and jewellery considered fashionable.

Perhaps the concept of “fashion” is doing too much work, unable to carry its own conceptual weight. Perhaps it’s no longer helpful for asking the type of questions needed to understand what the world of fashion is (and what it could be). That’s not as farfetched as it may sound. Fashion itself has always operated on a significant degree of deliberate self-deception, for instance in prioritizing the fantasy of creativity over the reality of business. What’s more, at a time when culture sells more effectively than anything else, luxury fashion brands are re-positioning themselves as cultural movements. What’s left for the concept of fashion when fashion itself is anti-fashion? To paraphrase Deleuze: if a concept or category is no longer of use, we have no choice but to make others.

And then there’s the phenomenon of the independent, niche brands inhabiting the Present Forever universe. Is Evan Kinori fashion? What about Unkruid? If so, how? If not, why not? Noah Johnson recently predicted that good clothes and creative independence are the future of fashion. That doesn’t sound wrong. But it’s also not entirely right. Johnson’s prediction concerns the aesthetics of fashion, not the fashion industry. Some of his statements — “Samples will go into mass production. The racks and e-comm pages will be replenished” — suggest that even when undoing itself completely, fashion is going to remain exactly the same forever and ever. This, in turn, seems to imply that fashion’s eternal present is something we’ll have to accept as unavoidable.

It’s open question, of course, whether this aesthetic undoing can take really place without any industrial undoing. After all, good clothes and creative independence don’t come easy and aren’t up for grabs. They often require an attitude of sustained opposition to or willful ignorance of fashion’s rules, or both. Even when that’s not the case, independent brands are able to create a human connection — and that connection demands a scale that allows for care and attention as well as a method that sparks experiment and failure. That’s what makes them relevant. And relevance is exactly what’s both the most desired and most unattainable thing in big fashion.

Now, fashion can try to become anti-fashion, incorporating what’s different from it. Yet, it can’t move outside itself to occupy the place where that difference happens. This particular happening will always be elsewhere.

One such elsewhere is located in a studio space in the Kadijken neighborhood of Amsterdam. That’s where I met the Dublin-born “J”, one half of the duo that makes up Vp Texi. His partner “A”, who’s originally from Calgary, lives and works in Antwerp. It’s not immediately obvious what Vp Texi is. Look at its IG page or website (currently undergoing some changes in preparation of the release of a new version of the ‘B. Hound Ear Hat’ later this week). What is clear, however, is that there’s very little to suggest it’s a fashion label. There’s no two collections a year, presented to wholesalers in Paris in January and June, for instance, and the rhythm is driven by trial-and-error creation rather than mechanized production. If it is a brand, it’s expanding the concept of brandhood to its maximum. If it’s not, it’s a collaborative art project whose output has so far taken the form of wearable objects, be it a pair of trousers, a t-shirt, a hat or a hooded scarf.

But Vp Texi started with a conversation about a boat.

Lukas Mauve (LM): “A” and you met at art school. Do you remember why you started Vp Texi?

J: I guess we started Texi to collaborate. We did know of each other and were on a head nod/handshake basis earlier, because we overlapped in Eindhoven when we were both studying (briefly) but didn’t properly become friends until meeting again in Antwerp.

We formally started Vp Texi in November 2023 and it originally stems from a conversation over dinner about our separate but aligned fascination with constructing our own one-person boat — and a (naive) interest in fibreglassing. These conversations led to an interesting understanding between us, and an eerily aligned frame of references, as well as a feeling of warmth towards the wear, details and aging of clothing. The progression to creating collaboratively came naturally and easily. We had both experimented with making clothing in our own regards but there was a confidence and progression of ideas that came from working together that gave us a push to produce the work openly, begin to sell to friends, friends of friends and not just for our own personal use.

LM: How do you think of Vp Texi? As a clothing brand? As an art project? Does it matter to you what it is or how it’s called?

J: For us, Texi is still in its formative stage. We look at it as an amalgam of our influences, passions and fleeting momentary interests, both separate and combined. This is translated at its core in clothing. That is our focus. But it is important for us to remain creatively limber and work outside of the context of clothing as we see fit.

We make clothing. The surrounding objects or experimentation is always predicated on building the world around the clothing, the context and general point of view we champion. But it is also intentional that these disparate outputs don’t essentially always “fit”. We feel comfortable to take leaps aesthetically and formally which, yes, probably stems from being rooted in different artistic disciplines and being self-taught. We are fabric-driven/sculpturally-driven/”I saw something interesting on the floor”-driven/ research-rabbit hole-driven, quite without hierarchy. It’s really an open-ended and ongoing dialogue.

LM: And how do you look at or think of what Vp Texi creates? Does it make individual objects? Or collections? Or something else?

J: We started the project by looking at our own daily uniforms. Luckily, we’re both the same size (L/XL) which helps greatly with sampling, as we can pass them between each other and compare notes. It’s structured at the moment in that we do discuss an “outfit” or uniform, and then go from there, building layers on top. These outfits however toe the line of hyper-practicality and something slightly more ridiculous, with many combinations not overly practical. I think of one drawing where the figure wears three differently fitting button-up Oxford style shirts on top of each other. This process is more of an exercise…and we always then think of the items in combination as layers. But they’re individually designed and tested to ensure they last and can be incorporated within a variety of contexts.

I think that a key thread running through our work is that a lot of what we make has the hallmarks of something that can be used on a daily basis. This is how we live with our clothing and objects, which leads to certain decisions in regards to adding or stripping back complexity and detail. Also knowing that there is a certain amount of absurdity in the every day, a sense of humor within the austerity of minimal work. So it’s a balancing act. We like consistency, but tend to find a stringent, non-developmental process quite uninteresting. We live with our clothes to refine them slowly — clearly, our sampling process isn’t done in one fitting, but rather through consistent wear.

LM: You both live and work in different cities. What does your collaborations look like on a day to day basis? What are the steps leading from an idea to a finalized object?

J: We visit each other often. Antwerp and Amsterdam are really very close. We also call regularly to discuss ideas and logistics. Honestly, we see it as an advantage. It splits our experiences and visual inputs. It allows us to draw from what’s happening in each other’s lives and cities. If we’d lived in the same place we’d probably hang out often.

Our first ideas usually come in the form of an image or a drawing that interests one of us. These are hardly ever clothing related. It can be a one sentence description that kinda floats in the air. Or an aspect or interesting detail that we find fascinating. We then discuss and leave time in between discussions for it to just hang in the air and be “figured out.” Next we usually find that we are in agreement on when to work on it, to tease out what it was exactly that we appreciated in the original source, and layer references and discuss options to build up or reduce away to a final item.

The common line running through these different moments in the process is a high level of trust in and appreciation of the other’s opinion, reasoning and point of view.

LM: Let’s look at some Vp Texi pieces — the first two already available, the third and fourth currently in process, if I’m not mistaken. One and two: the “Faucet Bottle” and the “Leather Fastener.” Third and fourth: the trousers and tie you’re currently working on. I’d like to get to the bottom of them. What sparked the idea? What made you decide to try and realize it? Where was the fabric sourced? What was the most enjoyable part of creating them?

J: Sure, let’s go through them!

The faucet spigot is simply a beautiful object. It enables us to offer a product en masse that is intrinsically unique. It originated from a combined love for the medical style, semi-translucent white version of the original Nalgene bottle. The diversity of shape and the almost floristic beauty of the antique spigot faucets, paired with the sterile perfection of the laboratory grade bottles, is very satisfying.

The “Leather Fastener” is a solution to our own problem of having wide pants that get stuck in bike chains. The shape is a hand-drawing. It’s laser-cut in veg-tan leather, sourced from offcuts at a local market. The nipple press attachments stem from our constant interest in peculiar hardware from leatherwork. It’s an open-ended object that can be used in a variety of ways, other than the intended one.

“A” has been making his own trousers for a long time, way before Texi. They’ve been “sampled” and tweaked over any years. The aim is to have a one-trouser life. The fabric is a very thickly woven cotton twill from Japan. It’s so thick it looks corduroy-esque. The fabrication will always change and there’ll be iterations in the future with deadstock and short-run fabrics. It felt important to us to make a trouser, which functions as the centre that the other offering branch off from. It’s our basis.

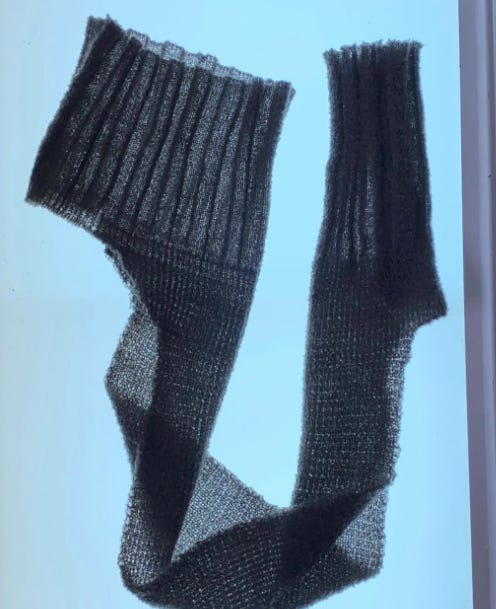

The ties came from an opportunity to work with an experimental knitting company in the Netherlands. “A” had recently bought some old wooden boat paddles in a second-hand store. It somehow felt fitting to commemorate them on the neck-ties. We ended up using a jacquard silk and land-wool combination, allowing us to layer references to 1950s jazz square knit ties and more 1980s-shape silk neckwear. The references are not just in the shape (which we did with an asymmetric end to the tie) but also in the materiality. It was a very generous offering from the workshop. But honestly the opportunity came with a very short time frame — so it was quicker than our usual process (idea to production in approximately 1 week!).

LM: And what about Vp Texi’s immediate and distant futures? Any objects you’d like to make, or stores you’d like to be stocked by?

J: Vp Texi’s future is not something we’re planning in a solid sense right now. At the moment we’re micro-sized, nimble and reflexive. This opens us to fast experimentation and quick response whenever an idea arises. There are no big dreams, just a steadfast belief in what we’re making and a contentment in the learning and growth that comes with starting a project of this sort. A permanent physical space to showcase our offerings would be swell. And we have a couple of stores in mind that would be lovely to work with, when the time is right and fitting. But again, no rush!

One specific object is quite obvious, of course — at some point we’ll find the time to get back to making that damn boat!

Thanks so much for joining this outsider’s path into the world of independent, off-beat brands and style. If you can, and feel like it, please consider supporting Present Forever by upgrading to a paid subscription. For just €5 a month (or €50 a year) you help make possible 1-2 monthly interviews, 1 weekly feature, and 1 weekly list of curated picks. It’s much appreciated.