PRESENT FOREVER is the new go-to source for discovering independent clothing brands, makers and stores from across the globe. Follow us on IG here and here

I’ve never been to New York. Everything I know about the city comes from books, magazines and movies, mixed up with stories, anecdotes and memories from others as well as dreams, emotions and imaginations from within myself. Perhaps it’s just a coincidence, but recently a number of brands caught my eye of which I only afterwards found out that they’re all based in New York. From that moment on, I could’t help but wonder how their New Yorkness contributes to their identities. I try to come up with answers in full recognition that I’ve no idea what New York is like, let alone what New Yorkness could mean. In lieu of a deductive logic, my reasoning proceeds inductively: I look at New York brand x, brand y, and brand z and then arrive at a very shaky generalization. Oddly enough, and however illogical, this way of going about does help make sense of how brand x stands out from the others. On the basis of a rough idea of what they have in common — in this case I’d say: a rural take on the New Americana — it becomes possible to see all kinds of smaller and larger differences, together giving meaning and adding depth to what they do and who they are.

One of the New York brands in question is archie, founded by Mark Smith Clarke. (Among the others, by the way, were Csillag, Carter Young and Grant NY.) Around 2020, when its first full collection had just been released, it was expected to be propelled into “New York’s if you-know-you-know epicenter.” Given the above, it’s impossible for me to determine from my own experience whether that prediction has come true. But if we take Colbo — the Lower East Side multi-disciplinary space — as one of the places gravitating around this epicenter, and knowing that they consistently stock archie, then the answer seems to be a definitive ‘yes!’. There are plenty of other senses in which the brand is shaped by, and part of, its hometown. It was begun out of a storage unit in Midtown in 2017-18. Today, all its limited-run batches of pieces are designed, developed and manufactured within a four block radius of Mark’s small studio in the Garment District. Here, he also does the lookbooks, modeled by a group of close friends and photographed by himself.

For a non-New Yorker living almost 6,000 kilometers away from the brand’s nearest stockist (let’s hope Nitty Gritty will change that soon) the go-to starting point for exploration is archie’s own website. Like the brand itself, it’s welcoming, done in earthly tones soft on the eyes, and full of attention to fabric detail. When you go there now, you’ll see two images: an outfit from the AW24 collection (‘Another Version of Pastoral’) and the front cover of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness (1943). This is a strangely fitting choice. Sartre was a prominent advocate of the philosophical school that prioritizes the existence of the human individual, studies existence from the individual’s perspective and says that, despite the world’s absurdity, individuals must still strive to lead authentic lives. Looking at archie’s past and present pieces, it’s almost as if they’re realizations of this existentialism: each in their own way, they’re highly individual and authentic, feeling like subtle forms of resistance against the kind of things that make our world so unbearably absurd.

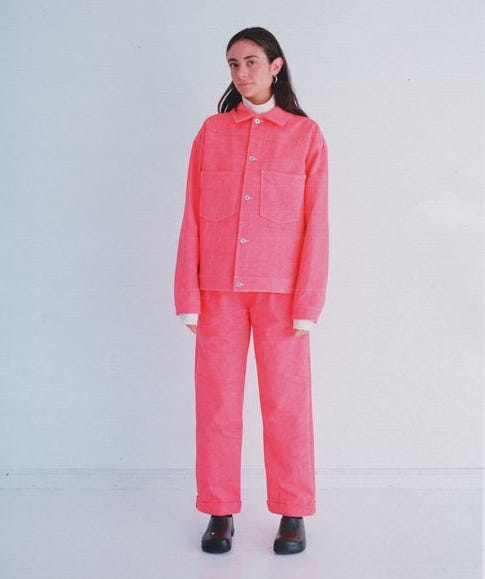

Archie also exists as a reminder of the complexity of simplicity — akin to the present-day challenges of leading a simple life. Take its ‘Chore Jacket’ as an example. A simple classic silhouette, it comes in ‘Cloud Organic Cotton Moleskin’, ‘Brown Organic Cotton Moleskin’ and ‘Burnt Umber Vegan Suede’, each produced in limited runs at a small, family-owned factory. The first two versions are made from a 100% organic cotton moleskin, woven and sheared in a 175-year-old German mill (also responsible for the cotton and corduroy fabrics used for the ‘Menard Coat’ and ‘Third Jean’.) Because of the machine needles delicately shearing the fabric until they have a brushed, suede-like face, the cotton is heavy (410 GSM) but satin-soft. The jackets have two large square patch pockets, one interior patch pocket at the chest, a large single vent, and feature Buffalo Horn buttons milled in Italy and herringbone tape from Japan. They can be combined to form an outfit with the ‘Post Pant’ (in ‘Cloud’ or ‘Brown’), a two-pleat trouser constructed from the same 100% organic heavy-but-soft cotton moleskin, featuring a heavyweight (250 GSM) chino cloth lining woven in Japan.

Or take any other piece, really. There’s the ‘Anorak’ (in ‘Violet’ and ‘Grey’). It’s done in a recycled wool-blended boa fleece from a mill in Japan focused on reducing raw material, with the finishing process of the textile taking place in Bishu, Aichi Prefecture. There’s also the ‘Sunday Shirt’, in three versions: ‘Khaki Cotton Broadcloth (Resin Finish)’, ‘Cloud Cotton Broadcloth (Resin Finish)’ and ‘Apricot Gingham Cotton Washer’. The first two are constructed in a yarn-dyed Japanese broad cloth cotton, where the single-ply yarns are rinsed in a resin and the fabric is then finished with a heavy wash and brushing to give them a worn-in feel. What makes the last version of the ‘Sunday Shirt’ extra special is that it’s free from any external dyes or processes: it comes in an undyed Japanese gingham cotton plaid with a crinkled texture, and features undyed Italian corozo buttons.

That’s the amount of dedication, attention, patience, and skill that go into creating “clothing for clothing’s sake,” as Mark put it in a previous interview. I reckon he’s himself very much a maker for making’s sake — doing things at his own slow pace, in his own gentle-yet-not-cutting-any-corners way. In our conversation over e-mail, I wanted to find out more about this ethos as well as the creative journey that led Mark from a small town in New Mexico to Colorado and then on to New York, and from engineering, photography and pattern-making to running an independent brand.

Lukas Mauve (LM): As someone writing about clothes without a formal background in fashion, I was pleasantly surprised to read that you’re a self-taught pattern maker. On Neighbour’s website I read that archie started as an “after-hours hobby.” I’d like to invite you to take me back to these years and tell me how archie turned from a hobby into a label? Was this the realization of a long-held dream? Or was it more like a sudden, happenstance experiment?

Mark Smith Clarke (MSC): “My path into this industry was neither a long-held dream nor a sudden experiment. It has been an amalgamation of slight adjustments and subtle corrections towards something subconscious that has at once felt very smooth and linear but is markedly jagged and revelatory upon closer inspection. I’m not sure where the exact moment was, but by the time the decision occurred to try and make clothing it already felt very obvious to me.”

“In 2015, I was in graduate school in Colorado studying chemical engineering and working weekends at a menswear shop. This combination of experiences felt useful, and exposed me to a balanced amount of CAD [computer-aided design] based technical work and more nuanced creative professionals. Through the shop (shout out to Daniel Armitage and Darin Combs) I was given the opportunity to move to New York in 2017 and work for a clothing label [Unis] that I really respected.”

“I think a broader answer to your question might be that I find the ubiquity of clothing to be very interesting. In so many ways it affects our human experience: Through modes deeply personal and sentimental, clothing can root itself within us way deeper than vapid materialism or trends can reach. And yet it presents itself outwardly in an unwavering, almost mundane blank statement: What appeals to you most regarding your own representation? A question that is asked every single day that you are alive. Even people who disavow the need to consider such questions still have to participate in them, and because of that hitch, clothing can act as this Sierpiński gasket for much larger truths than simple comfort, utility, or aesthetics.”

LM: Could you tell me a bit more about the shop in Colorado that helped smoothen your move to New York?

MSC: “Sure. The store was called Armitage & McMillan (run by Daniel Armitage and Darin Combs). It was one of only a handful of clothing stores in Colorado that emphasized a more refined version of menswear than what currently existed. They carried some things that didn’t immediately fit the bill for hard-line utilitarian outdoor gear, which was pretty much the entire lexicon of clothing in Denver (at that point, at least). This makes sense from a lot of perspectives, but their store was very refreshing to me. And the guys that ran it are great human beings; even before I worked there I would pop in and talk about Engineered Garments, Our Legacy, and clothing that was a little harder to come-by in the mid-2010s in Middle America.”

“All-in-all I worked there for about two years. Mostly weekends, though towards the end I started to work 20-30 hours per week — whatever hours I could get my hands on. This was from around 2014-2016. I was also a Teacher’s Assistant for undergraduate thermodynamics courses during that time period, at the University of Colorado Denver where I was in grad school. Grading papers, holding office hours, running a lab — mostly a lot of clerical work.”

LM: When you arrived in New York, what did you do to make a living and get things started, professionally speaking?

MSC: “I was doing E-commerce for Unis when archie began to take shape. [Unis, the brand known for its clean-looking pieces and founded in the Upper East Side in 2001, went out of business during the pandemic, in 2019.] It was a small enough operation that I could peer into fields I otherwise wasn’t qualified for. In fact, it was through that full-time position that I was afforded the opportunity to first interface with factories in Midtown Manhattan. During my lunch breaks I would hop on the train to the Garment District, walk into random buildings, take photos of the directory list and later contact anyone that felt relevant towards making clothes. This is also how I was introduced to design, pattern making and production. At the same I was operating a photo studio space in my home neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, called Wrythe Studio, that took up most of my mornings, nights, and weekends. So archie was effectively third on the totem pole of professional occupation for the first two or three years, but in a lot of ways that was a vital incubation period.”

LM: From the early beginnings of archie until today, you’ve done so many things yourself: you make each pattern in your studio, source the fabrics, do the trims, finishing, and photography. This type of personal dedication gives your clothes a certain kind of intimacy. At the same time, I can imagine it’s a lot to carry for you personally. What made you decide to work this manner?

MSC: “Because it felt like the path of least resistance for getting whatever was in my head out into the world. A decent amount of the wellspring for archie is fabricated from books I’m reading, most of which relies on my head to formulate an image of a character that is sometimes — but not always — well described by the author. It could also be a projective understanding of a topic that becomes representational in a combination with different fabrics, textures, colors, shapes, faces, and bodies. Conceptually, I liken it to the book Who Shall Know Them? by Faye Kicknosway, where she wrote poems from the perspectives of different people in famous Walker Evans’ photographs. From her author’s note: ‘The characters in these poems are imaged from the photos of Walkers Evans, but they have nothing to do with the real lives of the actual people.’ This free translation of source material feels very refreshing to me. It’s simultaneously real and totally made up, and when that’s the case everything resonates with potential meaning.”

“The perceived intimacy you mention is likely a byproduct of this method. Having been with each piece of clothing every step of the way allows me to better feel the weight of how much I’m making, and each decision that affects the outcome is considered more acute.”

LM: One particular aspect of what independent clothing designers like yourself do that always amazes me is the sourcing of unique fabrics. My question is simple, really: where do you start? Or, more precisely, what comes first: do you decide what kind of fabric you want for a certain piece and then search for it or do you browse through fabric samples and then decide what kind of piece to make with it?

MSC: “All fabrics for archie used to come from mills in Japan. For this most recent season, I worked with Kindermann Textil from Germany, a mill that has been operating since the late 1800s producing some of the most beautifully handed cottons I’ve had the opportunity to feel. I do still use Japanese fabrics elsewhere and mostly.”

“The start of the process is never really designated, it just happens. I’m always actively seeking new fabrics and feeling different things, just to get a better understanding of my own decision making. Like Kindermann, there are specific mills and reps in Japan I meet with a few times a year, and our relationship continues to grow stronger as we keep working together. Sometimes the decision is more esoteric, and there are symbolic gestures to using a specific type of fabric because of an attachment to historical processes or usages. Other times it can be an almost antithetical or absurd thought that can get the ball rolling, but the process starts when something feels like a touchstone. A piece of fabric that another fabric could potentially orbit, spiraling outward into something that resembles a collection of clothing.”

“This could also be informed by something in the production process; such as a better understanding of my manufacturing partners and their machines for optimized finishing techniques and better pricing breaks. After that, it’s all about costing. What may start out as 100-150 designs in my notebook slims down to about 18-24 samples per season after considering what is and what isn’t feasible as a product. I’m also still operating with such a low volume that, at times, I’m at the mercy of the mills and their capacity to work with me on smaller projects.”

LM: Another, bigger topic. There are many clothing brands in the world, and far too many (cheap, poorly-made) clothes. What was it that made you realize you were ‘on to something’ with archie. I’m probably asking because I’m struggling with this issue myself: here I am writing about clothes, knowing that there are people out there who’ve been doing this for many years, and not knowing what it is exactly that I can bring to the table. At the same time, I strongly feel that I cannot not do it — it’s an urge. How did that work in your case back in 2017-18, when you started archie?

MSC: “That’s an interesting question, and I appreciate the honesty. As it relates to archie, the real validation has always existed within, and I think that has at times been resourceful and at other times hindered the project’s viability. Internal validation can sometimes present itself orthogonal to other important external validations and figuring out how to serve both has been one of those jagged processes. From my perspective, remaining fixed on the original intent is the most important thing you can do. And as for the sentiment you laid out in the above question — I think this table only serves to distance the scratch from the itch. I think by simply just showing up to the table you offer a unique set of experiences and perspectives that were not there before you arrived, and whatever you lay down will be one of honest intention because of this instinctual gravity pulling you to your work.”

”And speaking directly about the sheer volume of clothing being produced in the world, it can be daunting for sure. But somehow that doesn’t seep into the calculus of how I think or feel about archie. If anything, there is maybe a bit of a reaction away from it, which made me hyper-focused on my constraints: making things within a 4 block radius of my studio, using small mills in Japan and Europe who pride themselves on their own sustainable prerogatives, and keeping production orders in small, one-off traditions. By tethering archie to these rules, it positioned my mindset as somehow existing outside the industry at-large, which is obviously wrong on its face but maybe an important initial distinction. The fashion industry is undeniably bleak from almost every vantage point, so some delusion can serve you well. Work hard, stick to your ideals, and you’ll find other people doing the same.”

LM: Thanks, that definitely resonates with me. But still…You say that the sheer volumes of clothes and brands doesn’t seep into archie’s calculus, yet the brand is unavoidably influenced by the world of which it is part. How do you keep your focus? What role do the origins of your own taste in clothes play a role here?

MSC: “I grew up in a small town in New Mexico, and my access to and interest in clothing was bound by big-box stores at our mall (Sears, JCPenney’s, Dillards — not sure if any of these will register with a Dutchman…) and mail-order catalogs (Eastbay, L.L. Bean, Orvic). Pre-internet era. While I can’t pinpoint how these exposures played into a more formative role, I do think they stood as an entry point to deciphering my own language from seemingly disparate sources.”

“My influences for archie can dip into the above outdoors brands — particularly mid-century American labels such as L.L. Bean, Orvis, Duxbak, Abercrombie, Russell Athletic, etc. But the bulk of influence is probably split between books I’m reading and daily life in New York City. One subway ride from my apartment to work can fill up an entire notebook with references — and New York tends to reward those who are observational. It’s a reason why I lean so heavily into working, and largely existing, in Midtown Manhattan. It’s at a rough point right now — lots of rampant drug use, homelessness, blatant disregard from a negligent administration — but remains such a beautiful cross section of human experience. It has somehow stayed the “New York City” inside much of the world’s mind, and it can be almost paradoxical with how things come together here. Things that wouldn’t make sense in any other context feel perfectly normal, and things that would be considered normal in other parts of the world can stick out like a sore-thumb.”

LM: To round off, let’s have a look at archie’s AW24 collection. If you’d have to pick one item to highlight, which one would it be?

MSC: “I try to hold an equal regard for all the pieces I’ve made throughout my time with archie, but for this question’s sake I’ll go with the one I’m most recently excited about. It’s a new outerwear piece released with the current AW24 collection called the ‘Menard Coat’ [available in ‘Black’ and ‘White’]. Menard is a small town of about 1,000 people in West Texas where I spent a lot of time with my dad and brother when I was a kid. These trips were primarily about getting outdoors, which meant a lot of heavy, extremely oversized Dickies canvas jackets and coveralls, most of them smelling of gasoline, smeared dirt and fish blood on the sleeves, a heavy cotton blanked lining inside. Canvas is a beautiful fabric for its temporal longevity and rugged simplicity, almost like a palette cleanser fabric. The one used for this coat is a heavy sanforized quality with an organic cotton/cupro plaid lining in the body and brushed peach poplin in the sleeves. Constructed with half-raglan, articulated sleeves and fashioned with two-way riri’s and Italian Horn buttons, it could make an argument for the most realized piece of clothing I’ve made and will last many winters after I’m gone. And maybe that sentiment is what I would like archie to represent in this world more than anything: the passing of time.”

Archie can be found at Colbo (New York City), Ships (Tokyo) Understory (Oakland), 88 Curate (Seoul) and its own online shop

thoughtful dude. incredible pieces.

One of the nicest guys I've met - great read!