This is the fourth and, for the time being, final part of Present Forever’s guide to contemporary independent Dutch fashion. Read about Camiel Fortgens, Peterson Stoop, Reverberate, Sine & Cosine, vp. texi, Newspeak, Delikatessen and many others in parts one, two and three.

No one knows what fashion is. You see it when you see it. But when you don’t see it, it’s as if there’s nothing to see.

That’s one reason why the simple question that started off this entire guide — what is Dutch fashion? — is so unanswerable. And by unanswerable I don’t mean to imply anything’s wrong with it, as if answerable questions are somehow better. I mean that it’s a question whose answer will consist of more questions. I’m convinced that’s a good thing. When it comes to fashion we need more answerability, for sure, but also less answers. Less people saying that this or that is fashion, and less believing that fashion is an answer to anything. After all, if it has answers to offer, it’s likely because the needs it produces come in the form of riddles we feel we need to solve before anyone else does.

You see Dutch fashion when you see it. But when do you see it? Where do you see it? What is it that you’re seeing when you’re seeing it?

Some of the people I’ve spoken with about these questions in the past few weeks didn’t care about them at all. That surprised me. At the same time, it didn’t. Today, the geographical place of clothing is fashion’s great divide — both of the greatest and least importance. The big money retail chains operating in the global market happily hide, ignore and neglect place into oblivion. All the while the place-and community-based approach of independent brands is exactly what gives them their aesthetic and critical edge.

It’s globalized fashion logic that makes the origin of a piece of clothing irrelevant, nay almost suspect. Of course, people are right when they suggest that the existence of Dutch (or American, or Belgian, or Japanese, or…) fashion shouldn’t be taken to imply that there’s something like an essential “Dutchness.” Yet, this needn’t culminate in the sentiment that place no longer matters in a globalized world, and that asking what’s Dutch (American, Belgian or Japanese) fashion is somehow wrong or redundant because of it. This question has nothing to do with wrongheaded nationalism, which after all is itself a by-product of a globalized logic. Instead, it has to do with its exact opposite, fashion’s local, particular and individual counter-logic. This logic teaches us that the era of total abstraction — of time that has ceased, of space that has vanished, of people that are dehumanized — is over.

A global village where there’s no time and space may be a wonderful reality, once realized. As an idea, however, it can do much harm, turning everything and everyone that’s here and now into an obstacle for a placeless and timeless world of nowhere and never. No coincidence, perhaps: McLuhan, the American sociologist and media theorist who coined the term, was hardly a utopian thinker. And he’s often said to have believed that, while we are all global villagers, some of us are more so than others.

Let’s forget about the question what’s contemporary Dutch fashion for now. Who knows, others or — why not? — I myself will explore it in the near future. This book makes a good start, though much more is needed, including the stuff of this four-part guide.

Let’s ask the more tangible, flesh and blood question: Where is Dutch fashion happening today? The obvious answer — in the Netherlands, that small, wealthy, stubborn, troublesome, odd and (according to the statisticians) happy country in Western Europe — is too obvious to count as an answer.

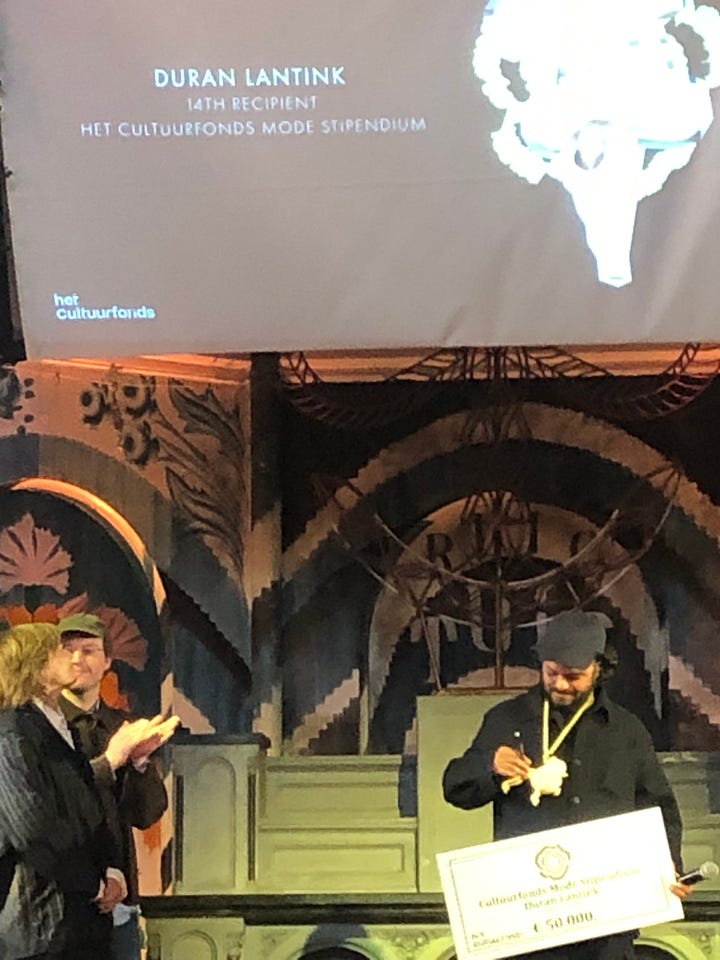

It’s true, of course, that Dutch fashion is spread across 33.500 square meters of flat landscape in the Netherlands, and a few hundred more in its Caribbean parts (Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten as well as the “public bodies” Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba). But it’s in many more places too, far outside, deeply hidden within, and at the fringes of the borders of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It’s in the African heritage that fuels Daily Paper’s streetwear designs. It’s in the “Caribbean couture” spirit of Rushemy Botter and Lisi Herrebrugh, the design duo behind Botter who have just been appointed creative directors of G-Star, the Dutch denim pioneer. It’s in Duran Lantink’s cut-and-paste, upcycling aesthetic, soon to be applied at Louis Vuitton’s Paris ateliers. It’s in Camiel Fortgens’ perfect imperfections about to take over that same fashion capital, having micro-shaped street style across Asia and the US for about ten years now. It’s in Ilanga, Fiasco Studio, Voddenmannen, Martan and Hul le Kes defashioning fashion, step by step, bit by bit.

Dutch fashion is everywhere and nowhere. It’s less present in the Netherlands than anywhere else in the world. It barely recognizes itself, yet it also prides itself. At times, it’s self-doubting, and at other times it’s self-congratulatory, without knowing which is which, without seeing that the latter is often an expression of the former. It’s been around for decades, but it’s only just waking up. Let this be Dutch fashion’s motto: when you wake up, wake up!