PRESENT FOREVER is the go-to source for exploring independent clothing and style. Become part of this off-beat universe by subscribing or upgrading here:

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Dutch fashion?

It might be haute couture designers like Viktor & Rolf, Iris van Herpen and Ronald van der Kemp. Perhaps it’s the latest rumors about Duran Lantink becoming Jean Paul Gaultier’s next creative director. Maybe it’s the raw denim of G-Star — the company co-owned by Pharrell Williams between 2016 and 2023 — or the streetwear of Patta — the label which celebrated its 20th anniversary last year together with Nike, its longtime collaborator.

Or you’re like me — a Dutchman born and bred in the Netherlands — and nothing specific comes to mind when thinking of Dutch fashion. This may be a sign of our ignorance, but I don’t think that’s it. And here’s why.

It’s one thing for globally recognized names like Viktor & Rolf, G-Star and Duran Lantink to be based in the Netherlands. It’s quite another for Dutch-based designers to have an aesthetic consistency that makes them — individually and collectively — representative or exemplary of “Dutch fashion.” Think of our southern neighbor Belgium, more specifically of the Antwerp Six. According to a famous anecdote, they rented a van and crossed the Canal to present at London Fashion Week in 1986. There they introduced a radical new vision for fashion that would come to define the 1990’s — a shared vision, closely akin to Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake in Japan, which looked towards the “down-trodden sub-cultures…to create high fashion.” A case could be made for an emergent “Dutch Front,” as Marcelo Horacio Maquieira Piriz did for A Shaded View of Fashion back in 2017, but chances are that its already surpassed by the “Belgian Three” now coming into existence — Marie Adam-Leenardt, Julie Kegels, and Meryll Rogge.

And that’s not even taking into account Glenn Martens at Maison Margiela, Nicolas Di Felica at Courrèges, Pieter Mulier at Alaïa, Anthony Vaccarello at Saint Laurent, and Julian Klausner at Dries Van Noten — or, by extension, Haider Ackerman, Demna Gvasalia and other non-Belgian designers who graduated from Belgian fashion schools. It makes this pretty cold statistic even colder: nul (read: zero, 0) Dutch creative directors at iconic fashion houses.

There’s something to Belgitude that’s winning. What about Dutchness? Is that even a word? It may be cliché to say that self-knowledge is much harder to obtain than an understanding of others. But it’s true. You need to stop and pause and occupy a position from which to engage in honest, systematic self-reflection. That’s not happening right now, partly because of a lack of basic infrastructure and mostly because of a very Dutch thing: the wish to be un-Dutch — the idea that something from the Netherlands can’t be really good as long as it’s associated with the Netherlands. This idea surely finds its roots in material reality: the country is both very small and a very big exporter. And maybe, who knows, we’re still in an era of cultural post-nationalism, which affects countries like the Netherlands quicker than larger countries.

Whatever it is, when it comes to representing the culture they come from, Dutch brands have complex work to do. Unlike America’s Americana, say, the Netherlands’ Dutchness is as conceptually vast as the country is geographically small (18 million people living within 41k km2). There’s Piet Mondriaan, grey weather conditions, local costume traditions, water engineering and Dutch Design as well as a long colonial history, geographically stretching to regions today known as Indonesia, South Africa, Surinam and Curaçao.

Back in 2007, when she was not yet Queen, Princess Maxima caused a lot of public discussion when she said: “The Dutchman doesn’t exist,” suggesting that there isn’t a typical common trait shared by each and every member of the Dutch population. Perhaps it’s the same with Dutch fashion’s Dutchness, once that would be a word with a meaning. It would not just be constantly morphing and evolving, covering anything and everything that loosely relates to the Netherlands — past and present — it would also always be internally heterogeneous and contested.

The same holds for “Tyrolean” and “Americana,” even though American brands do seem to adopt a welcoming rather than a critical stance towards phenomena related to the United States of America. Yet, if all such large-scale terms are equal, some of them definitely are more equal than others. Once it exists, it could well be that “Dutchness” — in the sense of Dutch fashion brought down to its nucleus — still doesn’t exist. It may capture something typical about clothing from the Netherlands. But that particular something will include things that are atypical as well.

So what’s atypically typical or typically atypical about Dutch fashion as it exists today? My thesis is that this question is presently best addressed by brands with hybrid, multicultural roots — Patta, Daily Paper, Botter — as well as by independent designers originally not from the Netherlands — Applied Art Forms, De Dam Foundation, Reverberate — and/or without a formal education in fashion — Camiel Fortgens, Sine & Cosine. Some of them are singularly able to create a sense of belonging to a community. Others are pushing the boundary of what contemporary luxury design is, and what it could be. Together, they’re a human force shaping Dutch culture in ways tangible and, especially, unimaginable.

The fact that joint reflection on how that’s happening isn’t happening also has to do — ironically — with Dutch fashion’s version of going Dutch. Each brand is participating in one and the same activity, but it’s organized in such a way that any sense of communal feeling is made impossible. A project like KledingCast is doing much to change that, but more is needed.

With this in mind, here’s the first part of a guide to some of the best independent Dutch clothing brands that you should know about — familiar and obscure, established and very young, and all pretty exciting.

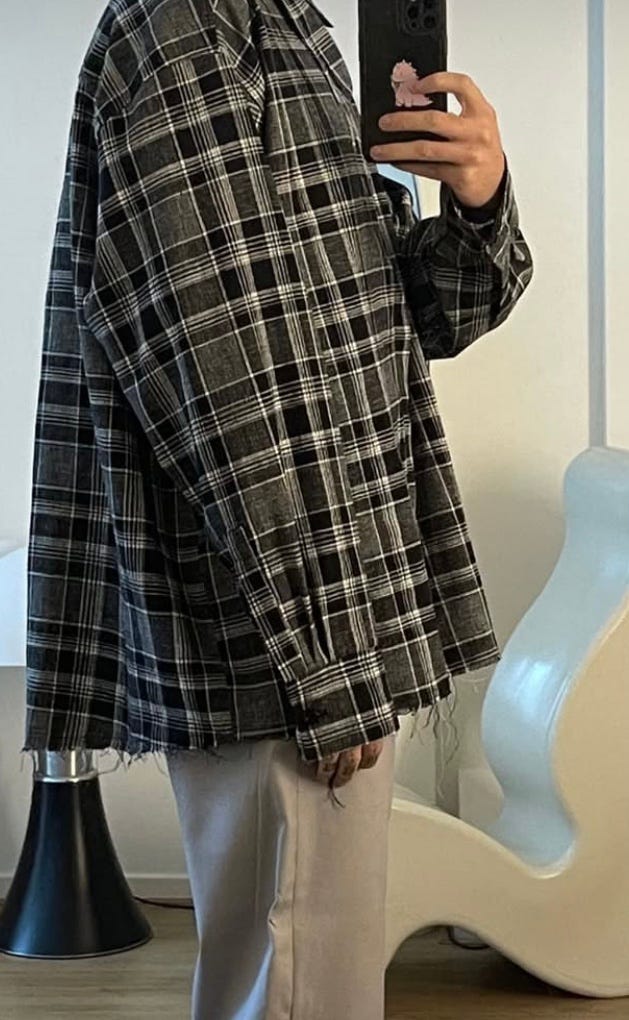

Founded in 2014, Camiel Fortgens is everybody’s favorite Amsterdam-based clothing brand — known for their reinterpretions of archetypal clothing, re-constructed into into unpolished, perfectly imperfect garments. Every single piece reflects Fortgens’ decision not to go to fashion school, leaving him with an approach to design untarnished by the industry’s rules, norms and expectations. Their colorful, light and slightly ‘70s-inspired SS25 is available now.

Is it a brand? An art project? An aesthetic experiment? I don’t know. The only thing I do know about Reinaert is that they are “playing tricks” and paying “a sincere tribute to the unruly.” The name derives from the mid-13th-century Dutch beast epic “Van den vos Reynaerde,” of which the label offers a “modern interpretation” wrapped in cloth. I’m intrigued.

As the geometrically literate will immediately expect, Sine & Cosine was founded by two mathematicians — both with no formal background in fashion. It’s reflected in their approach towards footwear: first they do a rigid analysis, laying bare the essential components, and then they synthesize, putting the components together to create something new with absolute precision and clarity. All designs carry this two-sidedness within themselves, as if they’re solving a variable on both sides of an equation: cerebral and expressive, minimalist and exaggerated, practical and aesthetic. They’ve their own online store, and at the moment are carried by three stockists — one in the Netherlands, surprisingly, and two in Japan.

Like Sine & Cosine, De Dam Foundation works with a definition of luxury that embraces timeless aesthetics as well as contemporary practicality and artisanal craftsmanship. Founded in 2022 by John Ro, who moved to the Netherlands from South Korea at the age of 18, the brand creates easy-going, hard-wearing foundational staples steeped in Dutch everydayness. The inspiration for their modular wardrobe comes from 18th-century paintings of Dutch fishermen as well as from the 20th-century modernism of Mondriaan and Rietveld. It’s something they share with Guy Berryman’s Applied Art Forms.

A new signature piece is this made-to-order brown sweater. It’s hand-knitted in Amsterdam from a virgin wool and yak spun in Germany, referencing the iconic Dutch gansey traditionally found in villages like Urk and Volendam.

Based out of Dordrecht, a city not far from Rotterdam, Alain Albèrt will launch its debut collection of handmade pieces this spring/summer (‘SS25 Mula’). There’s no website yet, but orders can be placed through IG. So far, there’s a wool kimono, a big work shirt, a harris big coat, and deck, heavy worker, poplin, and crinkle chore jackets — combining attentiveness to details with a heavily unpolished feel. The ‘Deck Jacket’, for instance, is made from a light creme 100% babyribcord fabric, tea dyed and washed with iron powder, and finished with bleach, grease and acryclic stencils. I just reached out to them this week to plan an interview, so stayed tuned for more!

Present Forever readers will know Vp Texi from this recent interview. It’s a public secret that they’re Unkruid’s little brother (or sister). They share a research-driven anti-fashion approach as well as an experimental sensibility steeped in deeply personal fascinations. Where Unkruid works in series of complete wardrobes — trousers, jackets, coats, shirts, bags — Vp Texi’s releases take the form of occasional drops, allowing a wardrobe to develop over time. Their online shop is up only now and then. Some items are currently available in limited batches: the ‘Leather Fastener’, ‘B. Hound Ear Hat’ (in various renditions) and ‘Knitted Neck Gaiter/Sleeve’.

The young Amsterdam-based brand Joone Joonam maximizes a Fortgens-esque aesthetic by merging ancient textiles, traditional crafts and historical costumes with societal and gender criticism. A lot of pieces are pretty out-there, but somehow it feels that’s not just for the sake of it: they’re like materializations of research, each in their own way inviting the wearer to experiment with selfhood and explore the boundary of their identities. That was my experience, at any rate, when I visited Joone Joonam’s studio some time last year. I couldn’t imagine myself wearing it. Yet, as soon as I wore it, I suddenly felt able to imagine myself differently. That’s what clothes are able to do, apparently. Give it a try every once in a while.

You’ve just read the first part of the Dutch Fashion Guide. If you liked it, why not subscribe or upgrade to support the creation of part two? Thanks!

Great great article !